Seeking Razor Clams on the Washington Coast

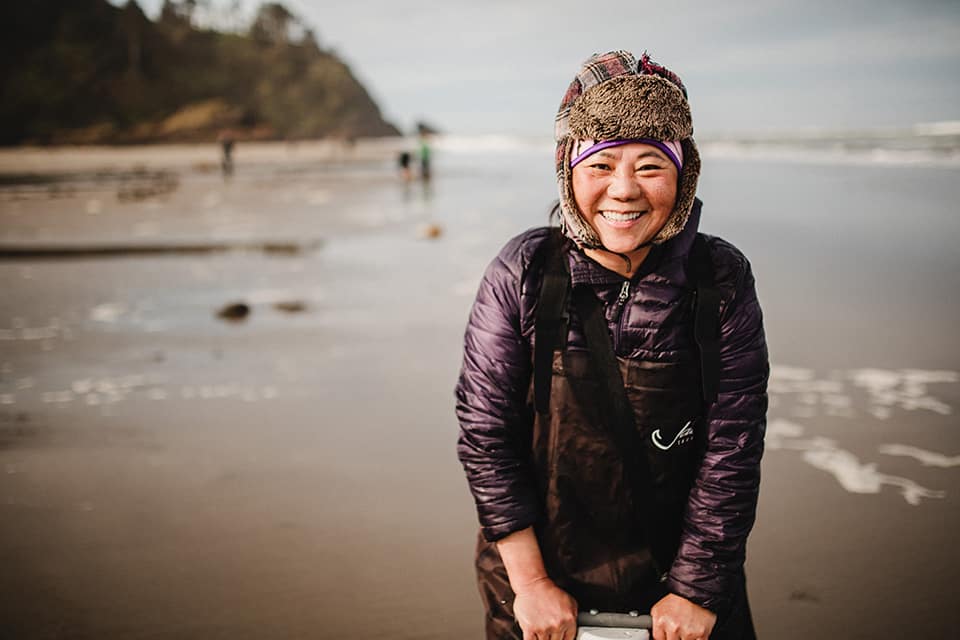

written by Mike Allen | photography by Bradley Lanphear

Washington’s Razor Clam History

The European history of the Pacific Northwest has been one of supernatural abundance, nearly exterminated. During salmon spawning season, pioneers wrote, Northwest streams appeared to be more fish than water. Camas lily blanketed the valleys so thickly, Lewis and Clark once mistook a meadow for an enormous lake. And on the beaches, said a journalist at The Oregonian, Pacific razor clams were dug out with plows and shoveled into wagon boxes.

Since Oregon biologist Vernon Brock went diving for razor clams offshore in 1938, it’s been known that huge reserves of clams live under many feet of water, safe from the digger’s shovel. The concern is that diggers’ ferocious appetites for these immensely rich and meaty treats can deplete the intertidal population at any given time. Washington regulates them more heavily than Oregon does, and as a result the digging there is generally better, and yields bigger clams.

The Vanishing Razor Clam

But on this May morning I’d driven up to the Long Beach Peninsula from Portland, and I’d been digging around with my clam tube for half an hour, and all I had to show for it is a sore upper back. It’s supposed to be easy: just look for a dimple in the sand, center the tube over it, push down on a handle across the top to force the tube into the sand and around the quickly retreating bivalve, put your thumb over a tiny hole in the top to create a vacuum, and pull. The tube comes up from the beach holding a cylinder of sand. Take your thumb off the hole, the vacuum breaks, and the sand cylinder comes sliding out, hopefully holding a fat clam.

This wasn’t my first clam dig, but it’d been a while. A massive and persistent toxic algal bloom off the Northwest coast had kept beaches closed to razor clamming for nearly two years, as test after test showed high levels of domoic acid, which can cause permanent short-term memory loss, and occasionally death. A brief reprieve in May allowed one weekend of low morning tides open for digging—fortunate for the peninsula since that also happened to be the weekend of the Long Beach Razor Clam Festival.

Razor Clam Openers

Even when times are good, razor clam openers are special events on the Washington coast. From October until May the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) opens specific stretches of low tides to razor clamming, usually three to four days over a weekend, and only for one low tide per opener—either morning or evening.

The Long Beach Peninsula has long celebrated the bivalve with a special fervency. Every clam dig creates a line of traffic snaking from Ilwaco, at the mouth of the Columbia, all the way to Oysterville, about 20 miles up the peninsula. Cars spill onto the beach itself as everything from sedans to super duty pickups cruise the hard packed sand, searching for the perfect spot. We’d rented a place in Ocean Park, just a brief walk from the beach, and although I tend to think the northernmost and remotest reaches of the beach must be the most productive, we opted to just walk down the road and clam right where we land. That might have been a mistake.

Although Willapa Bay oystering was the first natural extraction industry on the peninsula, razor clamming has been part of the draw for tourists since Henry Tinker opened the Long Beach Hotel in 1883. Wealthy Portland families would take a ferry from Astoria to Ilwaco and make their way up the peninsula, first by horse and carriage, then later by rail when the Ilwaco Railway and Navigation Company’s railroad opened in 1888. By 1929, Long Beach was such a popular destination, and clamming such a popular pastime, that the first limit was put on the recreational harvest: thirty-six clams per digger.

Today’s limit is normally fifteen clams per digger, per day, but on this particular dig, the WDFW had raised the limit to twenty-five. But the tide would turn in two hours, and if I was going to get a limit, I needed to stop wasting my time digging up empty cylinders of sand.

The Golden Age of Clamming

In 1949, when daily limits were lowered to twenty-four, diggers revolted. Likely they had never paid much attention to the limits anyway, but the Department of Fisheries (the predecessor to WDFW) had finally begun to crack down.

Officers reported tourists stuffing clams into their wader boots or dumping hauls into their cars before returning to dig again. One digger was busted with 300 clams. A commercial harvester on a boat dumped his haul overboard whenever enforcement came after him. He was finally apprehended, by seaplane, with 500 clams. Newspaper writers giddily punned on clams as slang for currency.

My first Clam

Finally I saw it: a living dimple, a clam retreating from the vibration of my footsteps. Holding my plastic clam tube by the small cross member at the top, I put the open end of the pipe directly over the dimple, and pushed down into the sand. The fact that it penetrated the surface easily was a sign that a bivalve was down there, and this “silo” of softened sand its lifelong home. I pulled the cylinder to the surface, kicked it apart with my boot, and grabbed a fat golden clam from inside.

From there, the digging went quickly, as the tide had gone out considerably since I started, and I filled my limit in less than an hour. From there it was time to help my little daughter dig some, as there are few things more adorable than a child marveling over the alien strangeness of some bizarre bit of wildness. As per the law, we took whatever comes up. Broken ones, crushed by the edge of the pipe as it chased the clam at an imperfect angle, and small ones, perhaps only two years old judging by the annular rings on the shell, went into the sack, along with perfect mollusks of satisfying heft.

Wasteful Clamming

Wastage is not only illegal, it’s highly frowned upon. A 1969 letter to editor at The Oregonian fumed that, “On every low tide, the Oregonians invade our beaches by the thousands. … They bring with them their wasteful methods of digging. They are the main reason the Washington authorities had to close the entire coast of Washington to clam digging last summer at the height of the tourist season.”

Those “wasteful methods” include discarding damaged or small clams in pursuit of a limit of fat and unblemished beauties. The problem is that even undamaged clams returned to the beach seldom survive, and become seagull or crab food.

The letter writer’s vitriol was directed at tourists, but the harm declaimed was the economic loss suffered by the tourism industry itself. Those losses, whether caused by clam wastage or not, are considerable. In 1964, it was reported that most of the lodgings in Long Beach had closed, with only the (still-thriving) Sherburne Hotel actively courting tourists. A 2009 study estimated the economic losses associated with recreational clamming closures due to toxic algal blooms totaled $24 million and more than 400 full-time jobs during just the 2007-2008 clamming season.

In fact, according to environmental historian Jennifer Ott, it was the Long Beach hotels and cabins, fearing the decline of their major tourist draw, that lobbied the state to conserve the resource in the first place, and the state responded. In addition to progressively tightening the limits, stopping wastage and imposing licensing and fees, Washington essentially barred commercial digging in 1964, limiting it to a few sand spits in the mouth of the Willapa Bay. The cottage industry of clam digging, driven by the canneries that existed primarily to can oysters, had been in decline for years, and tourism seemed a better economic bet.

Clamming Legacy

One of the people affected by the end of commercial clamming was the father of WDFW’s lead coastal shellfish biologist, Dan Ayres.

“I still have the shovel he used,” Ayres said.

Ayres manages the razor clam fishery, and decides when to open public digs. The challenge isn’t to keep the clams from going extinct, but to keep them abundant and large so that the digging is rewarding, and to protect the public health. Against these responsibilities, Ayres and the department have to balance the demands of the tourism industry. Too much restriction, and people go hungry, as was detailed in a recent piece in the Chinook Observer. During times of crisis, WDFW has been accused of everything from bureaucratic incompetence to actively trying to shut down clamming altogether. Talking to Ayres, it’s evident that the department does want everyone to get the most out of the resource. As evidence—the extra weight in my cooler thanks to the bonus limit during this too-brief respite from the toxic algae problem.

Back at home, standing over the kitchen sink, I began to clean the clams. Cutting sixty-odd clams from their shells, removing the viscera and rinsing away the remaining sand and partially digested food, butterflying each one, and packing them into containers for the freezer took me about two and a half hours. Abundance is indeed a curse. Then I rolled a few in buttermilk and breadcrumbs and fried them in butter, and the wisdom of our clam-digging forebears and the hungry greed of the forager was revealed in richness.