by Melissa Dalton

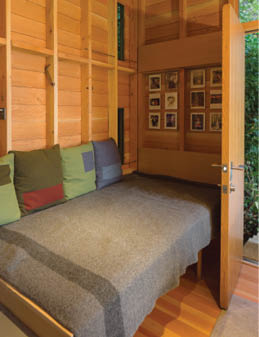

A tiny studio in the woods doubles as a bunkhouse. (Photo Art Grice)

Bainbridge Island: A home office that doubles as a bunkhouse

In 1976, architect Jim Cutler bought waterside acreage on Bainbridge Island. Some forty years later, he was struck by an idea while in his home office, then located in his daughters’ playroom: Why stare at an uninspiring view of salal and English ivy when he could be looking at the water instead?

Around the same time, Cutler’s 10-year-old daughter, Hannah, suggested he enclose her treehouse to become a base for sleepovers. The two notions entwined into an idea for a single building that both father and daughter could use. “I drew it up and then went back and forth with Hannah about ideas,” Cutler said. The result is a backyard studio in the footprint of an old garden shed, complete with a desk, single bed, wood-burning stove and glass-wrapped wall with a view of the sound.

“I’ve got to always be doing something with my hands,” Cutler said. When he first purchased the property, it had a small cabin and outhouse, complete with one running tap that drained to a cesspool. Cutler proceeded to hoist the cabin 10 feet in the air, using rented cribbing and two beams in order to build a first floor beneath it on a tight budget and expand the home to a comfortable 1,600 square feet. That project garnered an eight-page-spread in The Seattle Times and effectively kickstarted his Seattle-based practice, Cutler Anderson Architects.

For the backyard studio, Cutler’s wife, Beth, and Hannah joined him for the nine-month build. Beth and Hannah dug holes for the footings, while Cutler mixed concrete. He cut the walls and pre-drilled them in the garage so Hannah could screw them together. Cutler commissioned shingles cut from Corten steel for the walls and roof. “Hannah did all the sheathing until it got up too high for her,” Cutler said, so he finished up the roof. They installed all the windows except for the 5×10-foot piece of glass. That needed to be hired out, as it weighed 400 pounds.

Inside, Cutler detailed an exposed interior wood structure and hired his favorite cabinetmaker for the built-in elements. “It’s kind of a lifeboat,” Cutler said, meaning that from the wood stove to the battery storage, the bunkhouse packs all of the essentials in case of island brown-outs. “We really wanted a place where we could still live on the property and have heat,” Cutler said.

These days, the tiny studio is a communal spot. “The thing we didn’t expect is it became our family room,” Cutler said. When the wood stove gets going, the family’s cats come running, ready for a toasty snooze on the bed. After Cutler finishes work for the day, he sits at the desk and draws, while Hannah and Beth curl up and stream TV shows.

The 30-foot walk back to the main house is an opportunity to appreciate nature’s offerings. “I’m now trying to convince clients to do this. It’s no big deal to go outside from one area of a house to another,” Cutler said, describing a typical night: “The trees are howling from the wind. And there’s this moon with clouds rushing by. You have to stop and look. It just connects you back to the world.”

Seattle: A space ‘pops out’ to house an architectural studio

The “Pop-Out Studio” replaced a decrepit garage. (Photo Alan W. Abramowitz Photography)

Robert Hutchison has a penchant for exploration, even when staying put. For proof, look no further than the architect’s Instagram account. During Washington’s stay-at-home order to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in May, Hutchison started chronicling his “urban walks,” capturing a photo of an interesting building every mile or so. The resulting slide show is an immersive stroll along Seattle’s diverse—and sometimes quirky or questionable—streetscape, and also reveals Hutchison’s inquisitive eye. Perhaps, then, it’s no surprise that when the architect turned his gaze to the decrepit garage in his backyard more than a decade ago, with the goal of building a sleek new studio in its place, the process began with an art installation.

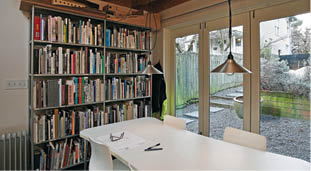

Four people work in the two-story Pop-Out Studio.

(Photo Mark Woods)

Such installations “give us a way to explore light and space at an architectural scale,” Hutchison said. Plus, they’re fun. In Hutchison’s hands, the rotted, rat-infested garage behind his 1912 farmhouse in the Fremont neighborhood became “Hole House #2,” wherein he drilled holes in two walls and the roof, then had a party. “And then the next day we tore it down,” Hutchison said.

The structure built in the garage’s place sits atop the old foundation. “The functional requirements were to try to provide as much flexible work space as possible in a super small footprint,” Hutchison said, as the studio is also home base for his firm, which currently numbers four people. To maximize the floor space, the two-story building cantilevers in two directions, a move which garnered it the nickname “Pop-Out Studio.”

for an easy commute. (Photo Mark Woods)

An alternating-tread steel ship’s ladder connects the two floors, and makes it possible to descend face out, which is helpful when carrying drawings or meeting notes in hand. The ladder also saves space in the 430-square-foot footprint. Desks line the perimeter walls and are surrounded by shelves weighed down with art and architecture books, making room for two conference tables, one up and one down, for simultaneous meetings to occur. Upstairs, a roof deck with a view of Lake Union is the spot for a private phone call, client meeting, or post-work happy hour.

“We have incredibly large quantities of glass on this little building,” Hutchison said. The incoming light penetrates via strips of windows and two sets of folding doors, detailed by Hutchison’s builder and friend Jake LaBarre. For those, LaBarre attached “super cheap and simple glass door panels” with a continuous piano hinge. The openings frame views of courtyards on two sides. The more narrow “sliver courtyard” along the building’s south wall is lined with a remnant of the former garage, sunlight filtering through the holes, edged with greenery and new growth.

Future use of the building is a question mark. If the firm grows, Hutchison might relocate, and his wife would move her home-based graphic design business inside. They may rent it out to local artists at some point, or, thanks to a change in zoning, build a 10-foot-wide house and attach the studio to it. The possibilities abound, but for now Hutchison is enjoying its current iteration and the brief walk to work, which leaves more time for other explorations: “Not having to commute is so incredible,” Hutchison said.