How Jason McLennan is saving the world, one building at a time

written by Melissa Dalton

AT FIRST GLANCE, the Bertschi School’s science wing seems like an ordinary classroom. It’s located in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood on a lot that was once an asphalt basketball court. Shouts from a nearby playground echo outside its walls. Inside is a whiteboard with scrawled assignments, wooden tables for students and a cluttered teacher’s desk in the corner. Diagrams of native Pacific Northwest salmon are tacked up for a fourth grade class. But that’s about where “ordinary” ends.

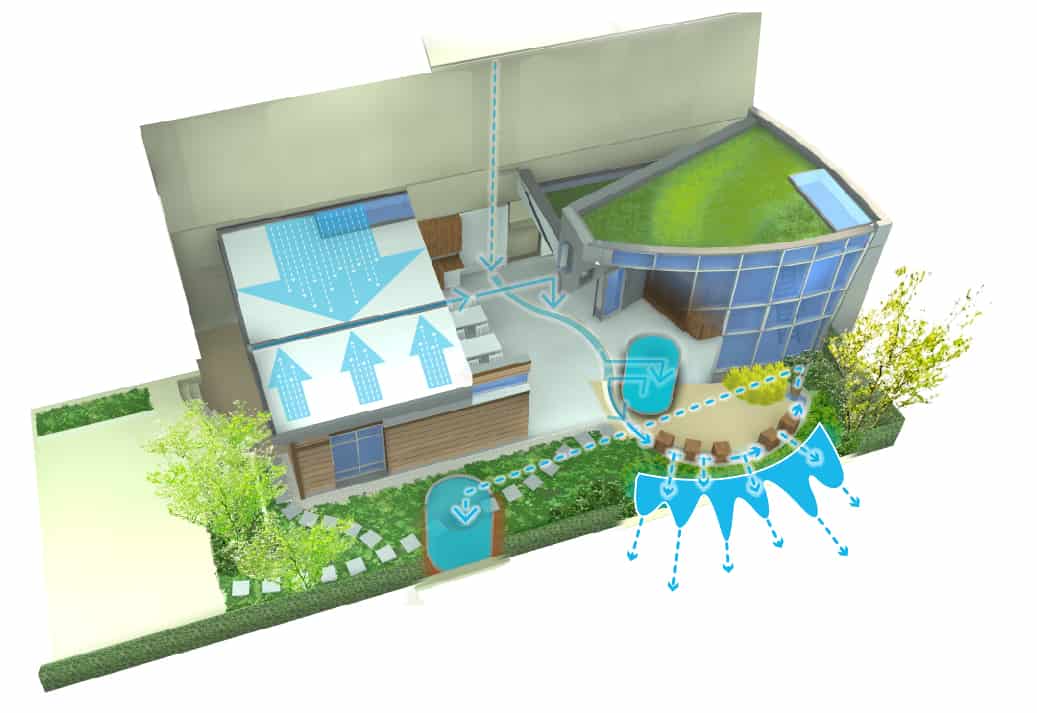

The out-of-the-ordinary begins with a 16-foot-high green wall, floor to ceiling dense with tropical plants that are treating the classroom’s greywater collected from the school’s sinks. Overhead, galvanized metal ductwork distributes fresh air drawn from outside and into the classroom. Underfoot, a runnel lined with river rocks snakes through the concrete, collecting water from the roof to irrigate the green wall and exterior landscaping. Topped in glass, the runnel frequently compels students to squat down and watch as water winds its way through the classroom, something that never ceases to fascinate the pre-K through fifth graders. “When it rains really hard and the water starts rushing, the kids will run in from recess to see it,” said Julie Blystad, the science specialist at Bertschi for twentyseven years.

All of these exposed systems are part of a “living building” curriculum and part of the most rigorous green building performance standard in the world. This Living Building Challenge is the brainchild of architect Jason McLennan. In order to achieve certification, a building must demonstrate complete self-sufficiency for water and energy use, only incorporate non-toxic building materials, and exemplify ideals of beauty and social justice, among other things. Laying down a Living Building Challenge in an independent grade school with a long history of sustainability just made sense. “This building gave us a chance to live what we’ve been talking about,” said Blystad. “This is the ideal.”

FROM THE TALLEST SMOKESTACK IN THE WORLD

The Living Building Challenge might not exist if Sudbury, Ontario weren’t such an environmental abomination. When Jason McLennan was born in Sudbury in 1973, the town was famous for two things— its environmental destruction and its smokestack. For a hundred years, Sudbury had been the world’s leading supplier of nickel. Mining operations had taken their toll, so the city built the smokestack in 1972 to reduce emissions.

McLennan remembers his hometown as a moonscape—its barren hills littered with tree stumps and open-pit fires of melting ore. “We would drive to other cities and they were always better than ours,” he said. “I think people had had enough of being the brunt of jokes.”

In 1978, Sudbury initiated the Land Reclamation Program in order to restore the landscape. The program called for an extensive process of liming and fertilizing the acidic soil, then encouraging natural colonization with seeding and annual tree plantings. McLennan participated in the latter regularly throughout his childhood, watching as Sudbury gradually reclaimed its natural environment through the years. “It left a big mark on me,” said McLennan. “I got to see the worst of humanity’s impacts but also the best.”

McLennan was born to a family of five, “to your pretty typical Canadian family,” he said. His father was a community college professor and his mother a nurse. The family wasn’t immune to the sweeping social consciousness of the time. “I had a family of vegetarians before it was cool,” McLennan said. While his two older sisters discussed animal welfare at the dinner table, he could be found designing things, first with blocks and later with a pen. It wasn’t long before he decided on a career path. “I knew what I was supposed to do by the time I was in the tenth grade,” he said.

The catalyst for his choice was a hill near his house. As a child, he and his class had planted it with trees. But when McLennan was in high school, a developer bought the hill and immediately cleared it of the vegetation, dynamiting the rock in order to level it. Then a parking lot and strip mall went up in its place. “It really upset me. It was so obviously awful,” McLennan said. “I thought, surely we can do better than this.”

After high school, McLennan moved west to study at the University of Oregon, which had one of the only sustainable architecture programs in the country at the time. “Oregon had a cadre of old solar rollers,” he said. “Some of the original thinkers from the ’70s.” After graduating, he packed up his U-Haul again. This time for a job in Missouri to work with green building pioneer Bob Berkebile at BNIM. There, McLennan became a partner after eight years, immersing himself in research and innovative sustainable design projects. “I had made it as an architect,” said McLennan. “So I quit.”

TO THE IMPACT OF A FLOWER

By the mid-2000s, green building had started to catch on around the country, gradually moving from a fringe interest to the mainstream. Even so, the same question McLennan had asked in the tenth grade dogged him as a professional. “I realized that it still wasn’t enough,” he said. “We weren’t winning the battle. And we were getting complacent because of the gains we had made as an industry.”

McLennan and Berkebile would have discussions about reframing people’s thinking. “We would talk about, instead of doing something that’s ‘less bad,’ can you define what ‘good’ looks like?” said McLennan. In late 2004 and into 2005, he started doing just that, writing a manifesto on nights and weekends. “It just kept bugging me,” he said. “There was no construct that helped people understand what success could look like.” His thirty-page essay would eventually become the codified standards of the Living Building Challenge.

In 2006, McLennan left BNIM to launch the Living Building Challenge from an educational platform, taking a job in Seattle as executive director of the Cascadia Green Building Council. The Challenge guidelines are intended to be an evolving set of standards that are meant to inspire ideas. “The Challenge gives people permission to be audacious,” said McLennan. After its debut, in Denver in 2006, he hit the road, speaking to audiences across the globe. The Kelowna Capital News, a newspaper in British Columbia, chronicled his appearance in September 2008 before a room of fifty people. McLennan told his audience, “The idea is that our buildings should have the impact of a flower.” The flower is the essential metaphor for the Challenge, as those pursuing certification strive to meet each petal, or category of significance. In the course of McLennan’s travels, the flower metaphor seized more than one attendee’s imagination.

In May of 2009, a young architect, Stacy Smedley, heard McLennan speak at the Living Future unConference in Portland. During the speech, he presented the idea that buildings could be more like flowers, to be ultimately restorative to the environment rather than harmful. “It struck a chord in me,” said Smedley. “I turned to my colleague and said, ‘We need to find a way to do this.’” A week later, they were taking a tour of the Bertschi School’s new LEED gold building, when the guide mentioned that they were considering a living building for their future science classroom. “It was this crazy fortuitous thing,” said Smedley. That fall, Bertschi and Smedley’s firm, KMD Architects, collaborated on the project, with KMD offering the design and pre-construction pro bono and Bertschi raising funds for construction costs. The team involved the students in the design process by asking the children what a classroom based on a flower would look like. Their ideas included a wall where something was always growing and a river running through the floor.

According to McLennan, today there are more than nine million square feet of living buildings in twelve countries around the world. These buildings will never have energy or water bills, have no carbon footprint, and are built with materials free of carcinogens. He’s about to break ground on his own flower—a “solar barn” on Bainbridge Island for a family of six. McLennan still travels for speaking engagements, but something has changed. For years, he was merely sowing ideas, now he gets to see them take root. “The most rewarding thing is to see people make the Challenge their own,” he said. “And to never know what they’re going to come up with next.”

For example, after the Bertschi project, Stacy Smedley co-founded the SEEDcollaborative, an organization that seeks to install portable living building classrooms around the country. It now has four in the works. Smedley was inspired to start SEED after a Bertschi student asked her why all buildings aren’t living. “These buildings are a teaching tool that can inspire people to be better stewards of the environment,” she said. “I had to find a way to make more kids ask that question.”

Sustainable architecture is the future!