Can endangered wild salmon & lower Snake River dams coexist?

written and photographed by Daniel O’Neil

Alongside Lapwai Creek, on the Nez Perce Reservation, Nakia Williamson stands overlooking a spawned-out coho carcass in the clear winter water. Here in the Snake River Basin, coho salmon were declared extinct by the early 1980s, so the Nez Perce Tribe used its hatchery program to establish a new lineage, a faint thread to a distant abundant past.

The Nez Perce are salmon people. Their stories tell of when the first humans arrived helpless, and chinook salmon offered his flesh to sustain the new people. Since then, the two have become one.

“Every spring, that order that was placed in the time of creation is renewed when the first salmon makes its way up from the ocean to the Columbia River, past the dams now, to the place where we are today, and fulfills that commitment the salmon made to us at that time,” said Williamson, director of the tribe’s cultural resource program.

“But it also obligates us with certain commitments as Nez Perce people, and part of that is manifested in the advocacy that we are having to do today as part of that responsibility that goes back to the origin of who we are as a people.”

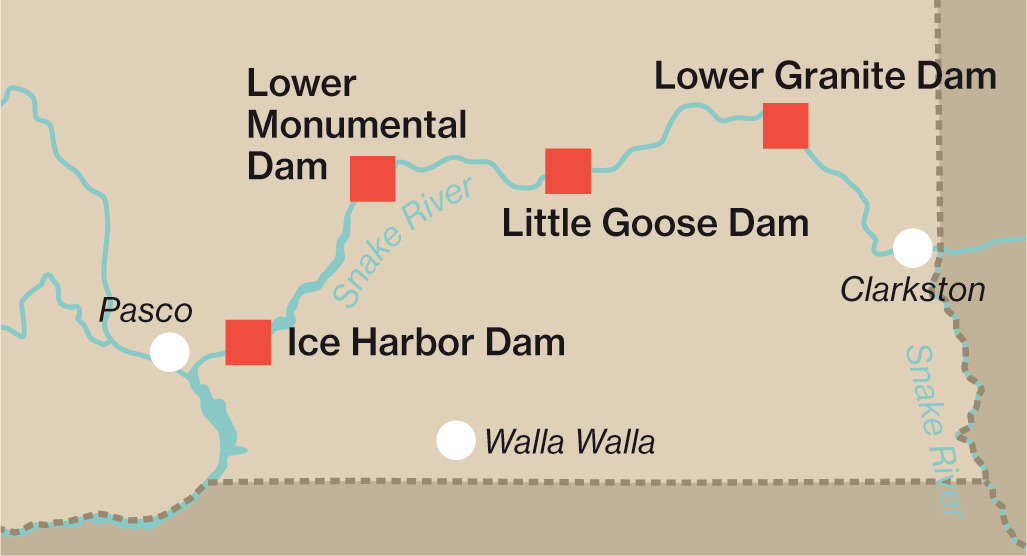

Between 1961 and 1975, a series of four federal dams—Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose and Lower Granite—abruptly interrupted the free-flowing lower Snake River, from just above Pasco to just beyond Clarkston, Washington. Approximately 150 miles of rapids, flood plains, orchards and Indigenous sites were replaced with silent reservoirs. As expected, salmon populations sank toward, or met, extinction.

Those who manage and benefit from the dams argue that the salmon’s real problems lie elsewhere and that replacing the dams is reckless. Salmon advocates and fisheries scientists insist that, having tried everything else, the only solution is to breach the dams—remove the earthen-fill embankment, mothball the rest—and replace their services before the wild salmon vanish. Pressure is building on Congress to decide the fate of these four dams, and which—wild salmon or dams—survives the rest of this century.

From the retreat of Ice Age glaciers some 12,000 years ago, until the mid-1800s, an estimated 2 million to 6 million collective salmon—chinook, coho and sockeye salmon, and steelhead trout—returned each year to the Snake River Basin, the largest tributary to the Columbia River. Throughout that entire time, Indigenous peoples like the Nez Perce have lived with, and off of, these fish. Snake River salmon fill an essential role in the Pacific Northwest, feeding forests and wildlife, including Puget Sound orcas, as well as commercial and recreational fishing families from Washington to Alaska.

By the late 1800s, the Snake River system began losing its salmon as overharvest, habitat destruction, small dams, pollution and other actions piled up. Downstream dams on the Columbia, along with impassable dams upstream of Clarkston, further restricted salmon runs on the Snake. In the early 1990s, all remaining wild salmon runs in the Snake River Basin were listed under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), which unleashed ongoing lawsuits.

The problem involves simple math. When two fish spawn and die, two of their offspring must return to replenish the population. Since construction of the lower Snake River (LSR) dams, wild salmon have not returned in numbers to replace themselves. Such a decline ends in extinction, as happened to the coho here and nearly to the sockeye.

With the dams, hatcheries were offered as mitigation. The Department of the Interior, and even the Washington Department of Fisheries, wrote memos about the necessary sacrifice of wild salmon for economic progress. Today, hundreds of millions of dollars annually fund hatchery programs throughout the Snake River Basin, producing hundreds of millions of smolts (juvenile salmon) each year. Since 1980, the federal government has spent nearly $27 billion toward restoring salmon here.

Hatcheries are not meant to replace wild fish or stop the extinction of a species, although a conservation hatchery program did save wild Snake River fall chinook, whose population has climbed from 100 to 9,000 natural-spawning fish. They have also kept the sockeye from extinction. Today, hatcheries produce the bulk of all Snake River salmon runs, yet numbers of hatchery fish returning from the sea still fall far short of mandated goals. Worse, wild-spawning Snake River spring chinook, once the lifeblood of the Nez Perce, face an uncertain fate.

A one-liter measuring cup sits full with water to its 1,000 milliliter mark. This represents the estimated one million spring chinook that historically returned to the Snake River Basin. Beside it is a similar, but empty, cup. Jay Hesse, director of biological services for the Nez Perce Tribe’s fisheries department, squirts 7.5 milliliters of water into the empty cup. “If each thousand fish is a milliliter, that’s where we’re at now, on average: 7,500 natural-origin spring chinook. It doesn’t even cover the bottom of the cup.”

He adds another 8.5 milliliters from the syringe, which represents the larger returns of wild spring chinook in 2022. “If you listened to the news reports that year, it was, ‘Wow, we turned a corner. We doubled the runs from the year before, from 8,000 to 16,000.’ It still doesn’t cover the bottom.” The ESA delisting requirement is 43,000.

At the LSR dams, workers are proud of their own figure: greater than 96 percent survival at each individual dam. This suggests that nearly every smolt passing over, through or alongside a dam survives the ordeal. The Army Corps of Engineers notes that all four LSR dams, plus the Columbia River dams downstream, meet or exceed this federal mandate. Yet they also point out that, on average, 27 percent of smolts die along the lower Snake.

“These fish do have an altered system, and that includes the reservoirs and dams,” said Christopher Peery, lead fish biologist for the Operations Division at the Corps of Engineers Walla Walla District. “But I think we’ve demonstrated that survival through the system is good for adults and juveniles if we manage them properly.”

With the installation of fish ladders, juvenile bypass systems, removable spillways and smolt transportation barges, the federal government provides some of the most high-tech and expensive fish passage on Earth. Yet Snake River salmon remain in trouble, and fish advocates believe the cumulative effect of these four LSR dams on top of the four downstream Columbia River dams proves too much. Adult return rates are two to four times higher for salmon in river systems below the LSR dams, like the John Day and the Yakima.

Peery blames the fish and birds waiting to feast on incoming smolts as the largest source of juvenile loss in the river system. But most of the salmon, he argues, are actually killed at sea. Some years, a cool and nourishing ocean produces more adult salmon, like in 2022. In other years, opposite conditions do the opposite. Peery points out that Snake River smolts have the added constraint of migrating a long distance. “They encounter more obstacles and have to go past more predators than other populations that migrate shorter distances. So they’re under more risks than populations that don’t have as many things going against them.”

Since the early 1970s, Steve Pettit, a Huey pilot in Vietnam and retired fish biologist with the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, has challenged the LSR dams, including the 96 percent survival rate. “That’s make-believe because they’re not looking at delayed mortality,” he said. After exiting a dam, smolts often emerge stunned or beat-up, which can lead to death downstream or expose the traumatized fish to waiting predators, dam after dam.

Pettit, who served as an expert witness in successful trials challenging Army Corps of Engineers dam operations after the ESA listings, suggests other factors at play. “There’s a lot of federal money involved, although a private consulting firm did the studies for the Corps and produced the 96 to 98 percent passage survival estimate,” Pettit said. “The fisheries agencies and the tribes have fought that figure for four decades. We don’t believe it, but the Corps paid their money for it, and that’s what they’re going to court with, that 96 percent of the fish that encounter the concrete survive.”

Although spawning in the largest wilderness area in the Lower 48, spring chinook are still struggling on the Salmon River despite low ocean harvest rates and zero harvest in the rivers, no hatchery influence, and dam-free access upstream of Lower Granite. A tributary of the Snake River in Hells Canyon, the Salmon hosts a population of spring chinook that remains incredibly wild. To spawn, they swim 900 miles, past eight dams, and gain 6,600 feet in elevation. Without their hereditary fitness and other genealogical traits, such a journey wouldn’t be possible.

Since 1992, spring chinook on the Salmon River, and across the entire Snake River Basin, have retained their ESA “threatened species” status. Today’s runs on the Middle Fork of the Salmon River average about 3 percent of what returned into the mid-1960s. In 2023, the return was half of that. Russ Thurow, emeritus fisheries research scientist at the U.S. Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station, has studied those chinook since the late 1970s. He is frustrated, yet not hopeless.

“The bottom line is these fish are at high risk of extinction, and analyses since the 1990s confirm that dams are the main problem preventing recovery of wild Snake River Basin salmon and steelhead. More recently, multiple plans have illustrated that virtually every service provided by the four lower Snake River dams can be replaced and mitigated,” Thurow said.

“In sharp contrast, we have no options to replace these iconic wild fish and the ecological, cultural, recreational and economic values they provide. If we lose them, they are gone—there are no populations on Earth that can replace them.”

In 2019, Thurow told The New York Times that the Salmon River’s wild chinook had another twenty years before extinction netted them. Today, he and other biologists figure those fish now have about fifteen years, or three generations, remaining. Nez Perce Fisheries biologists recently published a study that found 42 percent of the Snake’s wild spring and summer chinook populations qualified under the NOAA Fisheries term “quasi-extinct,” meaning fewer than fifty fish on spawning grounds for four consecutive years.

Peer-reviewed scientific papers, interagency committees, politicians ranging from Idaho Republican congressman Mike Simpson to Washington Governor Jay Inslee, and even a recent out-of-lockstep NOAA Fisheries report have all supported breaching the LSR dams as the only course toward recovering wild Snake River Basin salmon. Price tags for replacing the dams’ services range from $10 billion to $31 billion.

Last December, as part of an agreement related to ongoing litigation, the Biden Administration announced $300 million in habitat restoration and hatchery improvements over the next ten years. The White House cannot order breaching, but it did instruct federal agencies to investigate the scenario should Congress ever consider it. The federal government also committed $1 billion to funding tribally led renewable energy projects, including one created by the Nez Perce Tribe, sufficient to replace the power generated by the LSR dams.

On the surface, the four dams on the lower Snake River together provide about 900 megawatts of electricity annually, roughly enough yearly power for Seattle, or 4 percent of the region’s needs. But according to Bonneville Power Administration senior spokesperson Doug Johnson, on an annual basis the four dams generate 10 to 12 percent of the energy BPA is contractually obligated to provide—their sustained peaking capacity of around 2,300 megawatts allows for increased production in events like heat waves and cold snaps.

“It’s not a one-for-one replacement with wind or solar,” Johnson said. “The sun doesn’t shine at night, and you only have fuel for wind turbines when the wind’s blowing. Once we know how much water we’re going to have, we can plan and dispatch that output. You lose that with wind and solar.”

Gigawatt-scale batteries and small modular nuclear reactors could solve this problem, but those technologies are still in development. Johnson noted that it takes years to site, plan, design and construct generating resources like wind and solar farms, and that it can take even longer to adapt the power grid to this change.

“So it’s decades long, not months or years long, when you talk about a replacement of this magnitude. We need to take some of the myopic focus on these facilities out and look at all of the things that impact salmon and steelhead, and at other actions we can take to mitigate the impacts these and other dams have had on them across the Northwest,” Johnson said.

Replacing the transportation benefits of the four dams would also require significant investment and infrastructure. Shortline railroads once linked Palouse wheat growers to markets, until the dams’ toll-free navigational locks opened. In a new scenario, rails would carry cargo, the bulk of which is wheat for export, from Clarkston-Lewiston and ports downstream to westbound barges at the Tri-Cities.

Not everyone sees the crystal ball so promising. Derek Teal, general manager of Pomeroy Grain Growers, worries about the financial consequences for his sector and other industries that rely on barge transport to remain solvent.

“We’ve been in business since 1930, and we will not exist without the dams. And when I say that, people raise an eyebrow,” Teal said. “It won’t happen overnight, but without a viable rail solution, farmers will eventually go to places that are more cost-effective for them, which will erode away our business until we’re no longer sustainable.”

“Managed extinction,” fisheries scientist Rick Williams called it. “Slow enough for the people to accept the actions that were needed, and fast enough for the fish so that they could respond,” Williams said, quoting a former colleague. “That whole phrase applies to the issue on the dams right now. Murray and Inslee are saying, ‘No, slow down, we have to wait till we have all the energy replacement,’ and most of the biologists I’m talking to are saying, ‘I hope the fish have that much time,’ as opposed to starting lower Snake River restoration now and simultaneously attacking the replacement issues.”

Action did occur fast enough for salmon on the Elwha and Klamath rivers, where decision makers have prioritized wild fish over dams. But those rivers’ dams had no fish passage, and they cost more than they provided. In the case of the LSR, Congress has far less incentive to decommission the dams, for now.

Scout Alford has grown up along the lower Snake. She is now 18, and she votes. Alford is also a member of Youth Salmon Protectors, a collective of high school- and college-age Snake River salmon advocates. It is becoming her generation’s turn to influence Congress, including in the Pacific Northwest where breaching is still politically unpopular.

“If you can have clean energy and keep salmon from becoming extinct, why wouldn’t you take the measures to do that for future generations—for myself and my kids and my kids’ kids?” she said. “Why not move forward?”

Composed in impeccable cursive on thirteen line-ruled, light blue pages, the first treaty with the Nez Perce (Nimiipuu), in 1855, carries the implacable weight of the U.S. Constitution. In Article 3 of this agreement between sovereigns, the right to take fish is secured.

“What one side does should not burden the other side; there is mutual benefit to one another,” said Shannon Wheeler, chairman of the Nez Perce Tribe. “So if we understand it as healthy, harvestable, abundant numbers of fish in the water, then that’s what we expect. And if we’re unable to realize that benefit that we bargained for, the United States, which also is in the treaty, needs to remedy what has been wronged.”

In 1855, the right to fish for salmon implied a subsistence fishery for the tribe. Then and today, it also guarantees a way of life, a connection with the land. Having lived and fished along the Snake River for some 16,000 years, the Nez Perce Tribe recognizes this decisive moment to uphold its oath to salmon.

“We’ve reached our tipping point of how long we could live with the dams,” Wheeler said. “The irreversible damages the dams cause are more detrimental than the use that they provide. But the technologies and ingenuity that we have today are greater than at the inception of the dams. We just need the will to change. It’s not going to be an easy journey, but it’s a journey that we have to take nonetheless.”