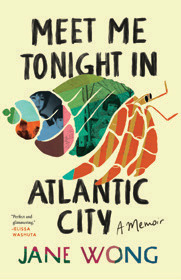

Jane Wong’s third book is a new love song of the Asian American working class

interview by Cathy Carroll

Jane Wong is based in Bellingham and Seattle, and her newly released third book, Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City, is a memoir. She holds a Ph.D. in English from the University of Washington and is an associate professor of creative writing at Western Washington University.

Tell us about how your memoir addresses casinos targeting low-income immigrant communities and your father’s gambling.

My family’s story and my father’s gambling addiction felt like it was part of something even larger, something systemic. Even as a young child, I sensed this. In writing this opening chapter of my memoir, I dove into personal memories but also quite a bit of sociological research. In a way, I was trying to find some answers—or rather, I was searching for a way to understand what drew him toward casino tables instead of us.

Casinos blatantly admit to targeting Asian American communities, offering free bus vouchers and hotel stays. It’s heartbreaking, really. So many readers have shared their own stories with me already.

Writing about this, through the personal and the collective, has been really powerful. From the title chapter, I write about the casino buses in Seattle: “When I’m grocery shopping for anything that reminds me of home—persimmons, sour dried plums, Chinese pickled vegetables—I swear I see my father boarding that bus, loafers polished in kitchen grease. I take one step closer to see better, hugging my groceries to my chest. But then: another. He looks like my father too, leather jacket and all. In this misty city, it’s hard to tell. They’re all my father.” I think of my father, who is not present in my life, often. I miss him. I miss who he could have been and who he could be—beyond gambling.

How much did you identify with Bruce Springsteen’s music growing up?

I was born and raised on the Jersey Shore—and went straight from the hospital to the restaurant I grew up in. I mostly grew up in Matawan, Eatontown and Tinton Falls. I lived there until I left for college in upstate New York. Atlantic City was where we went when my father gambled—mostly due to the casinos offering free hotel stays so he could lose more money. I’ll always be a Jersey girl, but I also feel like Seattle is my home.

As for Bruce Springsteen, of course I adore the Boss! He’s such a storyteller. And, as a poet, lyrics are so important to me. I feel like his songs honor working class folks. His acoustic Nebraska album was really influential for me. There’s this one lyric from “Mansion on the Hill” where he sings about looking at the fancy houses amid factories: “Rising above the factories and the fields/Now ever since I was a child I can remember/That mansion on the hill.” That reminds me of how my mother would drive us to the beach, past all the mansions in Rumson in our busted car that didn’t have A/C … and we’d “ooh and ah,” stunned by such wealth. Growing up in a family where we lived paycheck to paycheck, this was wild. His song “Atlantic City” also tells a story about debt, family and hope.

You wrote that when you were born, your mother held you up to the fluorescent light and declared: “I’m afraid. She knows too much.” Do you agree?

I love this story that my mom tells about my birth! Apparently, I didn’t cry and just stared at her with giant eyes. I wonder what that baby Jane knows. Writing the memoir, I engaged my own memory, research and also asked my family to recall certain moments—particularly the sensory details. Memory is so tied to our senses; when I asked my mom about what it was like working in a factory when she was a teenager, she remembered the smell of warm bread (a guy who had a crush on her brought her bread after her shift).

Memoir writing is all about choices—choosing which memories to give meaning to. And sometimes the smallest details became the most important throughlines. As for your last question, I think I know everything and nothing at the same time! Writing feels like that … I always write to discover something I wasn’t expecting.