Preserving the Past: How to remember and celebrate the mixed legacy of Hanford

written by Sheila G. Miller

Hanford. Long shrouded in secrecy, this 586 square miles of desert in southeast Washington played a pivotal role in World War II and the Cold War.

It was the site of incredible scientific and technological advancements that dramatically changed the United States and the world. But the work that happened here wasn’t without consequence—it created the plutonium used in the nuclear bomb detonated over Nagasaki, and production of that plutonium and other nuclear weapons rendered it a Superfund site with 56 million gallons of nuclear waste. Hanford officially stopped producing plutonium and electricity in 1987, and today is known as much for the multibillion dollar cleanup as it is for the incredible backstory on how that waste came to be. Now, the federal government and a diverse group of community members are preserving the mixed legacy of this storied, if silent, place, with both the Manhattan Project National Historical Park and other efforts.

Hanford’s History

Mike Mays runs Washington State University’s Hanford History Project. Mays grew up in Washington, went to high school in Pullman and earned degrees from the University of Puget Sound and the University of Washington. Still, when he got to Richland for his appointment at WSU-Tri-Cities, he didn’t know much about Hanford. “My wife is from Alabama, and she was doing research and had to explain to me some of the details of the significance of the Tri-Cities and Richland and Hanford,” Mays said. “I was just shocked. Having grown up here and taken Washington state history in high school and to know really so little about what had happened was kind of shocking to me.”

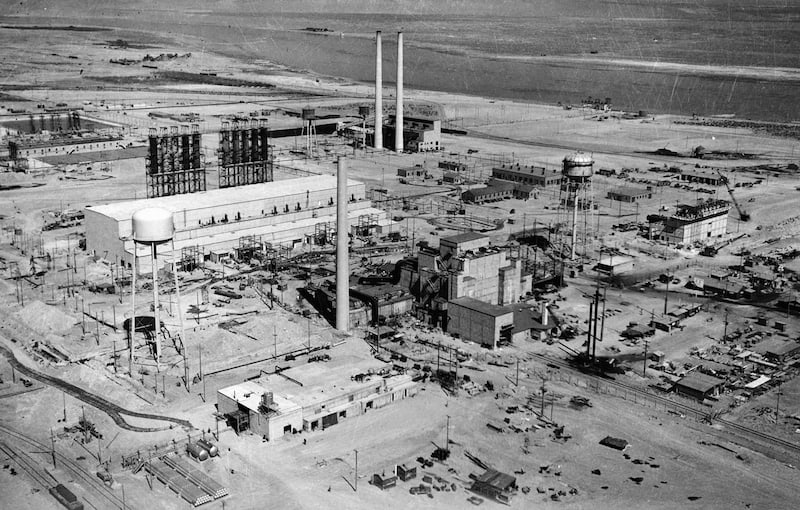

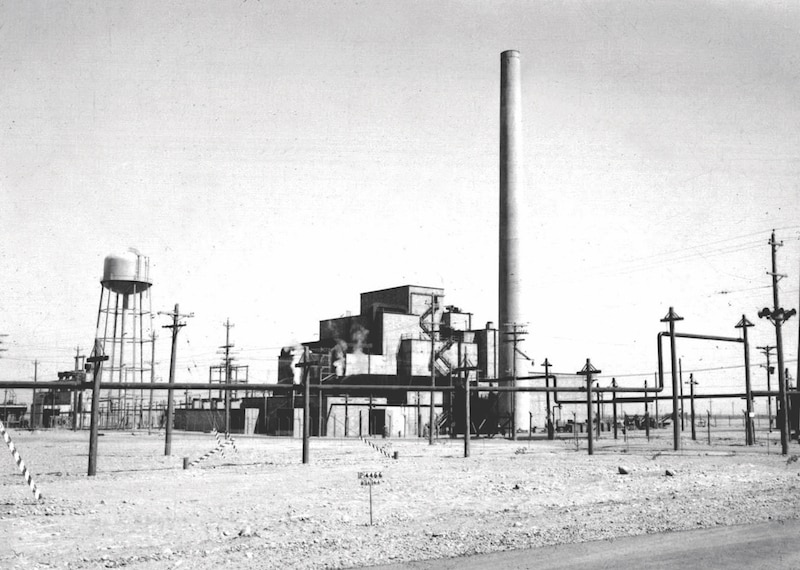

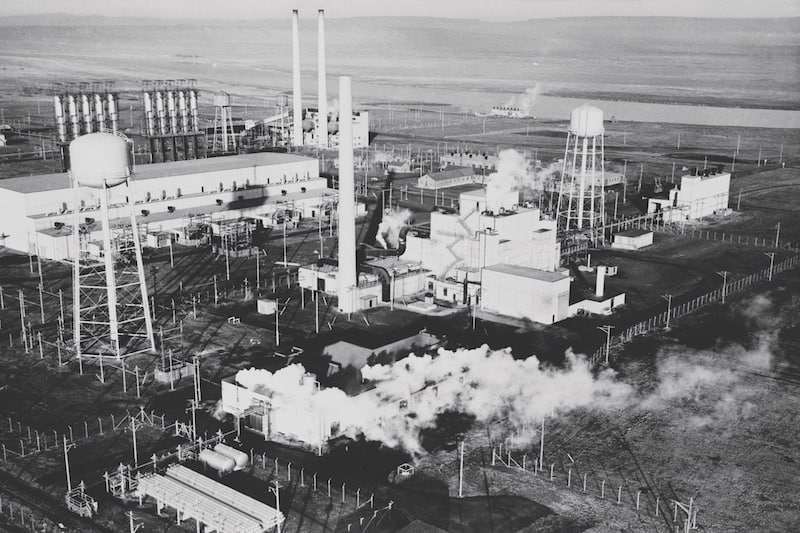

photos courtesy of Department of Energy

The site was selected by the federal government in 1942 for its role in the Manhattan Project, a program to develop nuclear bombs in response to the Germans’ discovery of nuclear fission. Hanford, along with Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Los Alamos, New Mexico, were secret locations dedicated to figuring out how to harness the power of nuclear fission and create the bombs that eventually brought to a grinding halt World War II. When it was selected to house this section of the Manhattan Project, residents of White Bluffs and Hanford were given thirty days to leave their homes and farms in early 1943 and given a small amount of money to do so. Then, it was time to recruit the workers—eventually 51,000 people in all. Many knew little about what they might be building or what the facilities would be used for.

According to the federal government’s official Hanford website, making plutonium is ineffcient—that is, to make a little plutonium you have to create a lot of waste, both liquid and solid. The site continued to create plutonium during the Cold War, and today about 8,000 employees continue to decommission, decontaminate and take down the buildings used to make the plutonium. That means making sure the waste doesn’t get in the air, water, or ground. But Mays, like many who grew up here, had only the vaguest notion of all this. So he decided he could prevent other students from having that aha moment later in life. As an administrator, he searched for ways to build academics on campus, and found a natural match—advancing the history of Hanford. Community groups around the area had given oral histories, but there was no central clearinghouse. “ They were tucked away in shoeboxes in people’s garages and attics and so forth,” Mays said.

The Department of Energy created seed money to help the Hanford History Project begin conducting oral histories, primarily focused on the residents who lived in Hanford and nearby White Bluffs before 1943. The project collected the oral histories hiding in people’s homes, as well as its own, all in one place. They’re now digitized, transcribed and on a website, www.hanfordhistory.com. WSU-Tri-Cities also offers a freshman interdisciplinary seminar course that focuses on Hanford history. Students work on semester-long projects devoted to the Manhattan Project and the area’s involvement in it. “While there are many people who know very deeply the history within the community … I would say most people are not fully aware of what the importance of the Manhattan Project was, not only for the community but for the world,” Mays said.

The Hanford History Project also facilitates research and manages the Hanford Collection—3,000 unique artifacts collected from the Hanford site between 1997 and 2014, dating between 1943 and 1990. Pieces from the collection are loaned out to museums, and the project continues to gather papers from notable Hanford alums. To Mays, preserving Hanford’s history is a simple choice—he believes the Manhattan Project was the most significant event of the twentieth century. “ There’s a lot of competition for that claim, but the discovery of nuclear ssion and the development of nuclear weapons fundamentally changed the way that we experience life,” he said. Mays believes there are several reasons Washington natives and other members of the public don’t have a strong understanding of the signi cance of Hanford. There’s an idea in Tri-Cities like many other places, Mays said, that “if it happened in my backyard it can’t be that interesting.”

There’s also the fact that the project was so secret for so long—many people didn’t know that relatives worked at Hanford, or if they knew that’s where they worked, they didn’t know what they did there. Mays also points to Hanford’s mixed legacy, and believes sometimes the humanitarian and environmental questions overshadow the scientific advancements made there. “After Three Mile Island in 1979 and Chernobyl in 1986, there was a reconsideration of nuclear that was absolutely called for,” Mays said. “Nobody can argue with people’s concerns. … A lot of the story just gets eclipsed because of the very legitimate concerns of downwinders and the effects of not only the bombs that were dropped on Japan but the prolific testing that happened after that, and the impacts that had on communities from the Marshall Islands to Nevada to Washington and so on and so forth. It shifted the pendulum.”

Now it’s about trying to get the pendulum back to the middle, Mays said—where the public can consider the incredible science and technological advancements made while also recognizing the humanitarian issues and environmental problems that came from the Manhattan Project. “ The Tri-Cities community has been a little defensive, and they have some good reasons to be. It’s a community where the nuclear industry has been its lifeblood, first with the Manhattan Project and then with nuclear energy, and then with the complete reversal—with the cleanup,” Mays said. “So the tendency has been to focus a little bit more on the heroic, the Greatest Generation and the engineering and technological feats. at shouldn’t be discounted, but that’s only one part of the story. Likewise, if we only focused on contamination and the bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, again that’s only one side of the story.”

Preserving B Reactor

Mays wasn’t the first person in the Tri-Cities to realize the importance of preserving Hanford’s history for future generations. For more than twenty- ve years, a group calling itself the B Reactor Museum Association toiled in an effort to prevent the site’s destruction. The association is primarily made up of people who worked at Hanford, though it is open to anyone. John Fox, president of the B Reactor Museum Association, described the group as a grassroots effort to persuade federal authorities that instead of sealing it and forgetting about it, they should save just this one reactor. It took years, Fox said, and a lot of help from engineering societies around the country, to get the building designated as a historic engineering achievement. “It was a very high-risk gamble from the standpoint of physics and chemistry,” Fox said of the reactor and the rest of the site. “It was taking something from the very forefront of scientific research at the time to mass production on an industrial scale.”

photos courtesy of Atomic Heritage Foundation

After the reactor was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1992, designated a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1994, and named a National Historic Landmark in 2008, the B Reactor opened for annual public tours in 2009. Not all of the building is available for tours—due to hazards—but the control room and much of where the action took place is open to visitors. Today, association members are still called on for special tours. Fox hosted a tour for Mitsugi Moriguchi, a survivor of the Nagasaki bombing. The year the bomb dropped, the Japanese visitor was 8 years old, while Fox turned 18. “I expected to be drafted to invade Japan, but the bomb was dropped in August and the war was over in September,” Fox said. “I wasn’t drafted, and Japan wasn’t invaded.” In other words, Fox said, the bomb affected his life in another way—he could very well have been killed in combat if the war had gone on.

Creating a National Park

The B Reactor Museum Association worked with a variety of groups in preserving the reactor. Chief among those is Cindy Kelly, the founder and president of the Atomic Heritage Foundation. Kelly started the foundation in 2002 with the mission of creating a Manhattan Project National Historical Park. Over the past sixteen years, the foundation has worked to preserve properties at Hanford, as well as in Oak Ridge and Los Alamos, and worked with the local communities in those places to preserve and interpret the history. The Atomic Heritage Foundation also has a huge online presence, offering up primary source documents and oral histories to the curious—want to see Albert Einstein’s letter to FDR warning of the German effort to make an atomic bomb? You’re in luck. Want to hear female physicist Leona Marshall Libby explain xenon poisoning? You’ve come to the right place. “I think by studying the past, we get a better sense for the present,” Kelly said. “Obviously we are in a world full of nuclear weapons, on the one hand. On the other hand, the world is full of the benefits—nuclear medicine and research—that were generated by the project.

photos courtesy of Atomic Heritage Foundation

Scientific innovations, high-speed computing, the human genome project, studies to understand what low doses of radiation can do in all sorts of contexts. All of these advances have been a direct descendant of the work done in the Manhattan Project, so it’s a very rich history.” The park was established in November 2015 after the Department of Energy and National Park Service came to an agreement on the project. DOE owns and manages the sites, while the park service handles visitor centers and interpretive services. In Hanford, the free, four-hour guided tours cover the B Reactor as well as several pre-Manhattan Project facilities, including the old high school and the Hanford Construction Camp Historic District. The biggest challenge of preserving Hanford, Fox said, came down to budget. The Department of Energy has a clear mission for Hanford at this point—to put its money into cleaning it up and packaging the 56 million gallons of nuclear waste that sit in underground tanks. “

That’s proving to be more of a challenge than building and operating the place in the first place, which is ironic,” Fox said. “Anything that doesn’t fit in that cleanup mission is harder to justify in the eyes of the federal agency, so (the park) took a lot of persuasion.” Kelly recognizes the controversies of the Manhattan Project, both environmental and humanitarian, but said it’s important to keep it in context. “What’s the legacy of Gettysburg, or Antietam?” she asked. “ The Civil War was a bloodbath. Talk about brutal—they were bayonetting each other and short-range ring. If you look at it now, that field is kind of bucolic looking and it’s hard to imagine.” As to the environmental legacy, she notes only 10 percent of the 580 square miles was used, and identified the environmental legacy of Hanford as one of advancing state-of-the-art environmental cleanup technologies. “Most of Hanford is pristine,” she said. “ There’s a section of Hanford that has flora and fauna not seen in the wild since the days of Lewis and Clark. It’s always been a little frustrating to hear the drumbeat that it’s the largest Superfund site in the world.”

When the idea of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park first surfaced, Kelly said the park service worried about putting rangers at a Superfund site. But, she said, there’s less radiation in the B Reactor than outside of it. “It’s not as bad as people think. Far from it,” she said. “That’s not to say there are not areas that are contaminated. The tank waste poses a unique disposal problem of what to do with it.” There is a section on the park’s website noting some areas are still part of “active DOE mission activities,” and as a result some of the facilities aren’t open to the public or can only be visited through bus tours. Fox hopes his group can help present more information about the environmental cleanup process, which Fox called “the fission product mess, which is the devilish problem here.”

“History is what happened and why it happened at the time, with the level of knowledge and understanding at that time,” Fox said. “Looking back at whether it should have happened or been avoided, we can always debate that forever. But what happened, happened. We aren’t necessarily memorializing it or lauding it by preserving it. It’s as important to preserve it as a reminder of the bad consequences it had and to say, ‘Maybe we should learn how to avoid doing these things when the next opportunity comes along.’” Kelly agreed. “It’s all part of our history,” Kelly said. “You don’t have to save everything—progress comes along. But I think it’s important to have something from every chapter. People are going to be curious about this, for generations to come.”