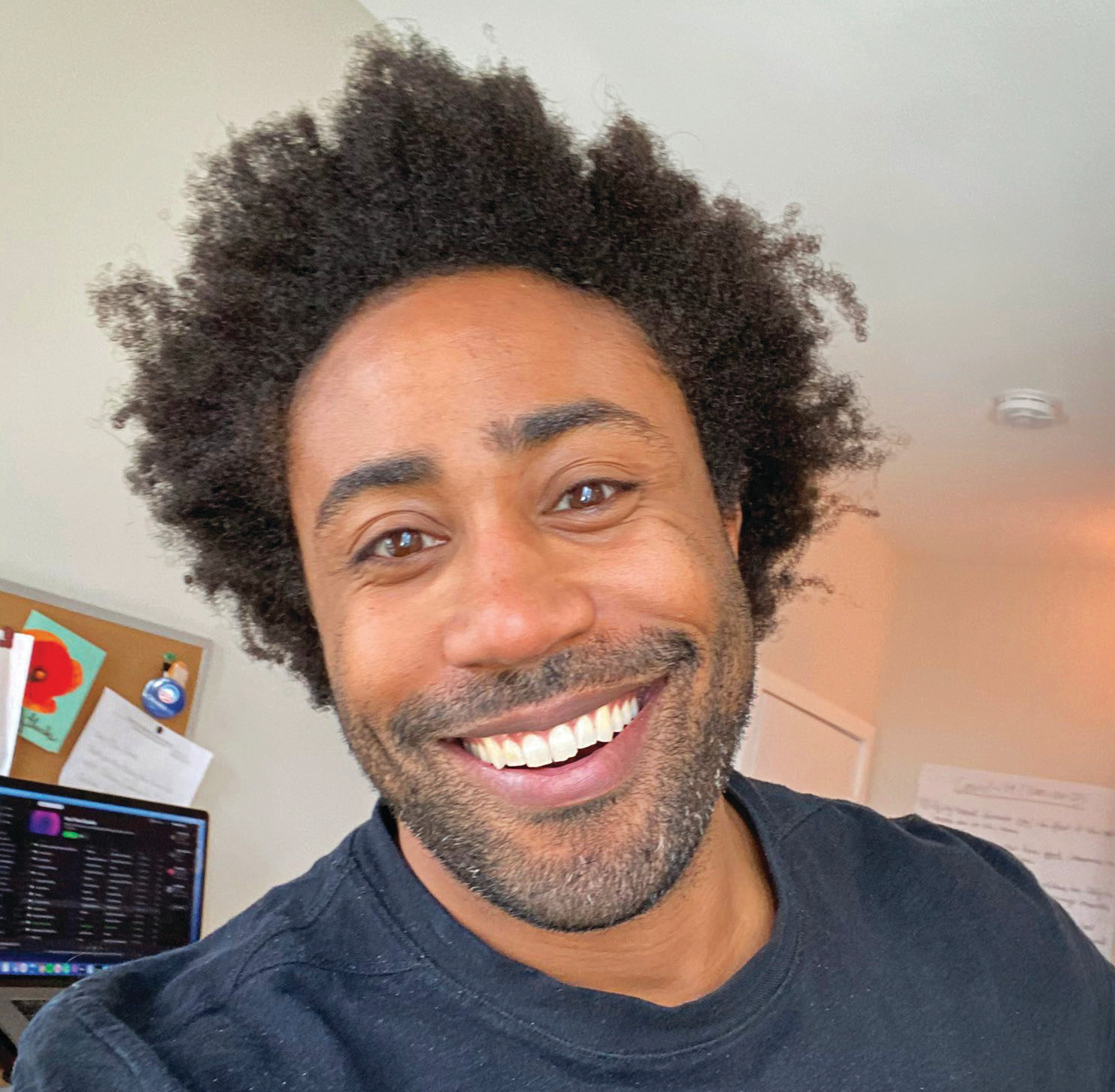

New King County homelessness leader, Marc Dones, harnesses radical empathy for social solutions

written by Kevin Max

In 2020, the county’s Point-in-Time tally, a measurement of people experiencing homelessness on a single day every January, hit 11,751, up 5 percent from the prior year. Since 2017, the homeless population in Seattle has remained between 11,000 and 12,000, with approximately half of this group describing themselves as without shelter, living outside.

In early 2021, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development told King County it did not have to count the number of people experiencing homelessness due to the heightened Co-vid risks to volunteers. If there were to be any year to put its head in the sand, this was it.

Shortly thereafter, King County hired Marc Dones, a person who local media immediately labelled as “unconventional,” in a county where the presumptive “conventional” approach was earning a failing grade. Some politicians were careful to give themselves political cover over Dones’ appointment by stating for the record that they disagreed with Dones’ approach on its face, but would otherwise find it within their professional mandate to work with Dones.

Yet, in a way, Dones seems the perfect person to address adversity with compassion. “My career starts from a place of doubt,” said Dones, who uses the pronouns they and them for reference. “A lot of why I do this comes from my own personal experience. I’m a queer non-binary Black person. I’ve been hospitalized twice for mental health stuff. I take a mood stabilizer every day, and part of my understanding of why I am where I am—whereas people just like me are somewhere else—is luck and a little bit of institutional capacity in my family.”

A Michigander who left for New York University to study psychiatric anthropology, Dones began working on homelessness issues in Massachusetts in the Executive Office of the Health and Human Services under then-Governor Deval Patrick. It was there, while working at the intersection of issues related to youth violence and youth homelessness that Dones had an epiphany.

“One of the things that became clear to me was that as I was doing that work, we were talking about the same young people,” said Dones. “In one meeting we were talking about one set of behavior patterns, and in another we were talking about another set of patterns, but the young people … were the same young people.”

The more Dones got into homelessness policy, the more problems with conventional approaches they saw. “What I realized was that homelessness policy in this country is a graveyard. It is where every bad policy goes to live forever as some weird zombie.”

He encountered many well-funded policies that offered many services but little housing for homeless people. “I became fixated on housing policy because, in my understanding then and now, if we can fix that phase, the ripple effect on our policy landscape will be massive.”

In Seattle today, Dones encountered an administrative patchwork that lacked cohesion and focus. “What I found was deep fragmentation and a community that was full of mistrust because of that fragmentation,” said Dones. After five interviews with various King County and homelessness agencies, Dones saw a path forward by creating the area’s first regional homelessness authority, now the King County Regional Homelessness Authority (KCRHA), to bring together the administrative pieces under a common system.

Under Dones’ leadership, KCRHA hopes to coalesce regional partners around the notion that the problem of homelessness can indeed be solved in one of the richest areas in the wealthiest country. “We know how to end homelessness,” Dones said. “We’ve done it over and over again in this country, but what we have done now is that we have gotten rid of the tools that we used to do it with. And we’re asking systems across the country to perform these rabbit-out-of-hat tricks that will somehow house everyone without any housing. That doesn’t make sense.”

One of the biggest misconceptions about homelessness, Dones said, is that homelessness is a choice and that it’s a result of people making bad decisions and choosing not to avail themselves of the help they need. “The emergence of homelessness in its modern formation that started in 1982-83 as a result of the decimation of a lot of our safety net programs, the explicitly racist attacks from the NIxon and Reagan administrations and then the absolute loss of a fundamental housing pillar,” Dones noted.

In the early part of the twentieth century, America had a vast stock of single room occupancy, or SROs, that allowed people in transition to rent a single room very inexpensively over longer periods of time. “We used SRO stocks to house veterans coming back from two world wars, and that was primarily what we used,” Dones said. “The idea of homeless vets was not a thing because we had SRO stocks, we had the GI Bill, we had assets and resources that were not just appropriate, but were at scale.”

Today’s solution, Dones said, has to be one that prioritizes the housing problem to compensate for the decimation of SROs. “It has to be an equation of economics, supply-side dynamics and stabilization support,” said Dones. “It can’t just be a services conversation. There is no amount of services that ever becomes a home.”

Ultimately, Dones said, we can actually solve this—and that a communal will to end homelessness can become a powerful driver. “One of the things that Governor Patrick always used to say is that ‘Government is only what we agree to do together.’ I really think that we have the opportunity to come together as a region and say enough is enough, that this is unsustainable, inhumane and a full crisis that we have to stop.”

Perhaps King County’s homelessness quandary needs an unconventional approach. Perhaps the “unconventional” quality of Dones is the disarming persona that embraces human frailty and doubt and uses it as motivation to do more and do better.

“I have a fundamental doubt about my fundamental right to be in the spaces I’m in, and about my ability to do the things I do,” Dones said. “This is born of a deep and fundamental understanding that my trajectory easily could have been very different, and I’ve watched it turn out different for other people in my life. I think that thing that I wake up with that feels like doubt is a question of … is it ever going to be good enough that people who experience a different trajectory than me—who I watched during that time—will they get to benefit from the work that me and my team do?”