The Wild Collective

written by Tricia Louvar

On the shoulder of winter and spring, with my kids in school, I looked at a topographical map of Washington. Up close the contour lines of Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest resembled hand-picked molluscan seashells. So many wild places to enter. Where to start?

Excursions live on a spectrum of “wild.” It’s a fast and loose term. Are we talking one-too-many-cocktails-at-Bathtub-Gin-on-Second-Avenue wild? Or scaling Mount Rainier in August amid a blizzard? The word is relative. However, I lean to the more conservation-style of wild. I had diverse ecoregions in mind: marine West Coast forest, North American cold deserts and forested Western cordillera.

My research led me to the state’s National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) system, a conservation and education program of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, a federal agency within the Department of Interior. I tend to wander and favor areas with infrequent human sightings. Give me a fiery gathering of bluff mallow, rustling pronghorn antelope, dusty boots and thermos of coffee as entrance barriers of the wild. The Pacific Northwest has me wanderlust jonesing for its Greek blue alpine lakes in the Northern Cascades or the rustic A-frame cabin with an Antibes green front door in the Olympic National Forest.

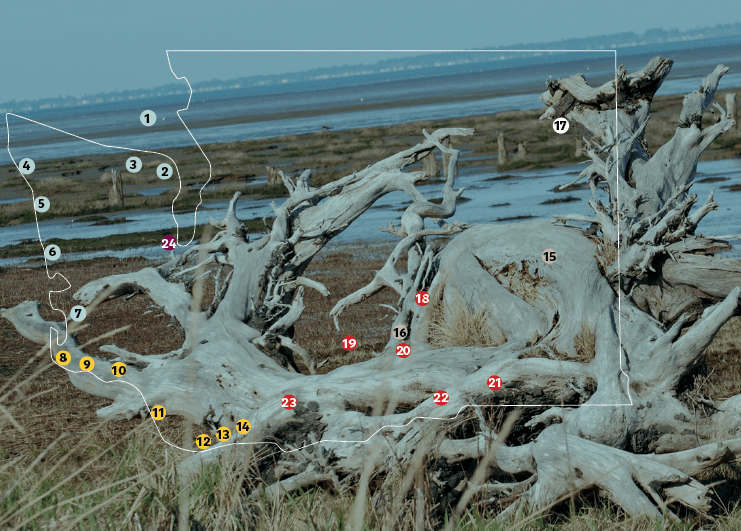

Each state has at least one NWR. Washington has twenty-four designated NWR areas all over the state. Flattery Rocks NWR, for example, is one of the first refuges founded by Theodore Roosevelt in 1907. Seabirds being ravaged along the Pacific coast prompted Roosevelt’s environmental action and placed executive orders along swaths of natural habitats for restoration and conservation. The avifauna and wildlife abound in these sacred sites. Today, the Fish and Wildlife Service manages more than 20 million acres of designated NWR wilderness lands across the country.

Given the immensity of Washington’s geospatial wonders, here are a few brush strokes of its coveted NWRs. As Rachel Carson, conservationist, environmentalist and biologist, said, “Wild creatures, like men, must have a place to live.”

Coastal Refuges

Proximity and similarities to regional ecosystems organize the NWRs. Think seabird-centric, puffins, seals; marine life diversity and stunning vistas. On the Washington coast, birders study the tide chart and arrive within the two hours of high tide to witness a flurry of birds. Grays Harbor NWR, for example, becomes a matrix of avian activity as hundreds of thousands of birds use the area as a seasonal migration spot from late April to early May.

Cold Deserts

The wide basalt plateau of the Columbia River Plateau or Columbia Basin, known as a cold desert, reaches far and wide from Washington, Idaho and Oregon. In these NWRs, expect to see shrublands, savannas and grasslands. The Saddle Mountain National Wildlife Refuge occupies 32,000 acres and has become part of the Hanford Reach National Monument, rife with paleontological artifacts from the late-Miocene to late-Pliocene.

Forested Western Cordillera

Forest covers one half of Washington, and even then it’s subdivided into specific regions, such as coastal, lowland, mountain or eastside forest. Trees are not just trees to Washingtonians. The dialed-in native or environmental scientist knows tree types by their elevation and moisture level. Western hemlock thrives in moist zones. Depending on elevation, thick evergreens bundle up or thin out, resulting in these forested treasures at Little Pend Oreille NWR in the far northeastern corner of the state.

Given my need for silence, breathing and lack of crowds, I think a springtime road trip to a collection of these refuges is in order. Sketchbook packed. Coffee brewing. Backpack loaded. May the light discharge itself and nests empty themselves with new life.

Visiting a National Wildlife Reserve

Check each NWR’s website before leaving to find if there are any alerts in the area regarding wildlife, weather or access. Stay on the trail, leave only footprints (no litter) and keep the appropriate observation distance, such as 100 yards between you and the wildlife. It is illegal to approach, feed or touch wildlife and sea animals. Do not disturb the wildlife on land or sea. Know the accessibility for people with disabilities. Bring binoculars.

Olympic Peninsula

- San Juan Islands NWR

- Protection Island NWR

- Dungeness NWR

- Flattery Rocks NWR

- Quillayute Needles NWR

- Copalis NWR

- Grays Harbor NWR

Southwest Washington

- Willapa NWR

- Lewis and Clark NWR

- Julia Butler Hansen Refuge for the Columbian White-tailed Deer NWR

- Ridgefield NWR

- Steigerwald Lake NWR

- Franz Lake NWR

- Pierce NWR

Eastern Washington

- Turnbull NWR

- Saddle Mountain NWR

Northeastern Washington

- Little Pend Oreille NWR

Mid-Columbia

- Columbia NWR

- Toppenish NWR

- Hanford Reach National

- Monument NWR

- McNary NWR

- Umatilla NWR

- Conboy Lake NWR

Puget Sound Lowlands

- Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually NWR