Award-winning children’s author Deborah Underwood says kids books must have it all—in 500 words or less

written by Sheila G. Miller | featured photo courtesy of Penguin Young Readers

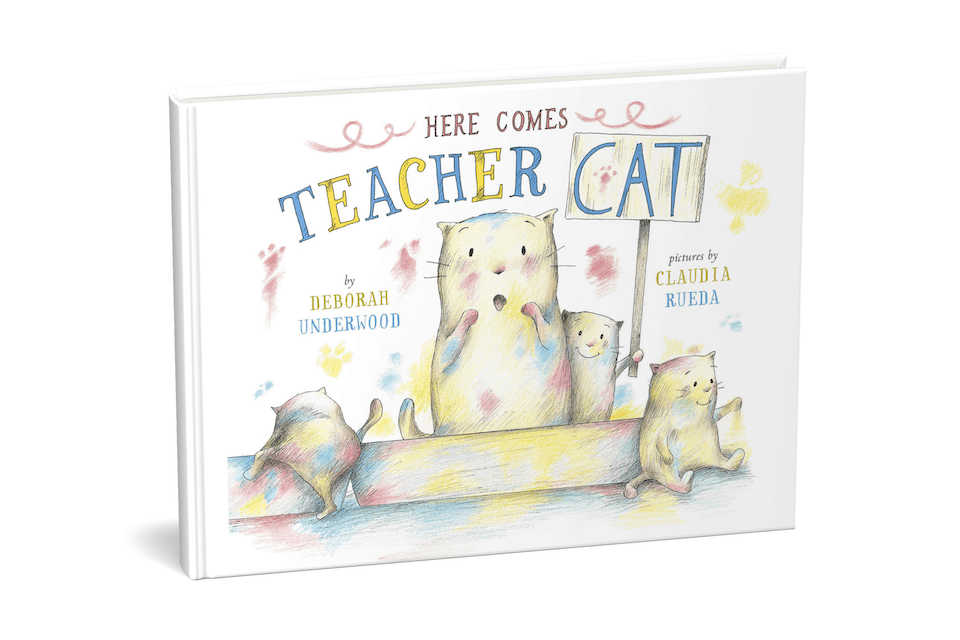

Deborah Underwood’s characters are no strangers to trouble. But then, some of them are cats and mice. Others are fairy-tale villains. Underwood draws inspiration from everywhere, and trouble finds her. Born and raised in Walla Walla, her recent book Here Comes The Tooth Fairy Cat won a Washington State Book Award for the early-readers category. She has ten picture books coming out in the next several years, including Here Comes Teacher Cat next summer, in which Cat needs to be a substitute teacher for a day; Super Saurus Saves Kindergarten, illustrated by Ned Young, out next year; and a few pieces in a middle-grade humor anthology, Funny Girl, out next May.

Deborah Underwood’s characters are no strangers to trouble. But then, some of them are cats and mice. Others are fairy-tale villains. Underwood draws inspiration from everywhere, and trouble finds her. Born and raised in Walla Walla, her recent book Here Comes The Tooth Fairy Cat won a Washington State Book Award for the early-readers category. She has ten picture books coming out in the next several years, including Here Comes Teacher Cat next summer, in which Cat needs to be a substitute teacher for a day; Super Saurus Saves Kindergarten, illustrated by Ned Young, out next year; and a few pieces in a middle-grade humor anthology, Funny Girl, out next May.

You started out writing screenplays—what changed?

After I graduated from college, I tried all kinds of writing. I sold a few magazine articles and some greeting cards. I wrote puzzles for Dell Puzzle Magazines for many years. I even wrote a terrible romance novel—it didn’t sell, for good reason!

Then in 1999, my sister in Scotland had a baby. I thought writing picture books would be a way to connect with my niece across all the miles that separated us.

Mainly I write for kids because I’ve always loved children’s books. In retrospect, it seems silly that it took so long for me to figure out I should write for kids. I suspect most grown-ups don’t listen to Paddington Bear audiobooks-— that should have tipped me off!

A lot of people assume that writing for kids is easier than writing an adult novel. What do you think?

People think picture books are easy to write because they’re short. But a picture book writer needs to create compelling characters, construct a solid plot with conflict, escalation, and resolution, and evoke an emotional response in the reader—and she has to do it in 500 words. One of my books is only eighty words long. It’s definitely not easy!

An interesting thing about picture books is that you’re writing for kids, but a 5-year-old doesn’t march into a bookstore alone to buy a book. It’s grown-ups who do the purchasing. So a book must—most importantly—bring joy to a young person, but it also needs to appeal to gatekeepers (parents, teachers, and librarians), because that’s how it will get into a child’s hands.

How do you work with illustrators?

Authors and illustrators usually don’t work together. The writer sells a manuscript to a publisher, and the publisher chooses the artist. The author and illustrator typically don’t communicate directly while the book is in process, because the illustrator needs the freedom to make the story his or her own.

But the Cat books rely heavily on illustrations to tell the story. When I write the books, I do my own sketches to show Cat’s signs and expressions. As a rule, an author would never send sketches to an editor unless she was an author/illustrator—that’s a substantial breach of publishing etiquette.

My agent decided my drawings were the best way to get the idea of the book across. We were also fortunate that the wonderful illustrator, Claudia Rueda, was open to working this way.

How do you come up with your stories and flesh them out?

Every story is different. The Cat books started because I couldn’t think of an idea. My cat, Bella, was sitting on my bed in front of me, so I sketched a cat while I waited for inspiration. The cat looked grumpy, so I asked why. The cat answered by holding up a sign, and the first Cat book was born.

I got the idea for The Quiet Book while waiting for a classical guitar concert to start. My 2018 book Monster and Mouse was inspired by a sketch an artist friend posted on Facebook. Interstellar Cinderella began with the title.

For each book, my general process is to do several drafts on my own, then take the manuscript to my critique groups for more input before I revise it again (and again) and send it to my agent. If the book sells, there are more revisions once an editor is involved.