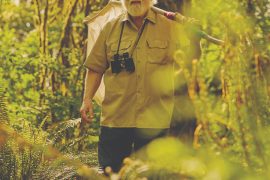

UW’s Scott Meschke made groundwater and virus transmission his life’s pursuit

Written by Kevin Max | Illustration by Allison Bye

As the pandemic raced through populations where virus testing was sparse, if at all, public agencies still had some indication of where new outbreaks might occur. In the absence of testing on a personal basis, sewage became the new crystal ball.

The concept behind the testing is fairly simple. Those who are infected with the Covid virus will emit tiny particles of it in their feces. When wastewater is collected from a building’s sewage, the presence of the virus can be divined through a number of tests. Without complications, the results can be known within a day.

Scott Meschke, an environmental and occupational health microbiologist at the University of Washington, had a jumpstart on Covid, having spent a career researching the detection of viruses in water and food. At University of North Carolina, where he received his doctoral degree, he worked on this problem through the lens of other pandemics.

“I started working on polio as a test organism, Meschke said. “It was a good model and historically defined. … The methods were translatable. We’re using techniques for other viruses and reforming them for Covid.”

Meschke loved chemistry as a high school student in Kansas. At the University of Kansas, he ended up focusing on biology and environmental courses. He went on to earn a law degree from Kansas, thinking he could change the world for the better as an environmental attorney. He realized that this profession was more about billable hours than saving the planet and paused for a moment. Then he read an article about viruses and groundwater and made that his life’s pursuit.

Today, more than sixty-five colleges across the country are using wastewater detection to monitor and minimize Covid outbreaks on their campuses, according to research by National Public Radio. This test can help identify early cases of the virus and lead to identification and isolation of the infected students to head off a more massive contagion.

The University of Arizona, for example, was able to avert a crisis when wastewater test results at one of its dorms came back positive. Subsequent individual testing of the 311 students found that two were asymptomatic carriers of the virus.

At the same time, Meschke points to the limitation of wastewater testing. “We get the most utility when we look at specific dorms or facilities that have their own wastewater systems,” he said. The results are most relevant when the people using the facilities being tested are the only ones using the toilets. As soon as one unknown, non-resident uses a toilet in a facility being tested, the results are less reliable.

“I’m proud of the work we’ve done with polio and typhoid and even with SARS-COVID-2,” said Meschke. “We’re injecting a certain amount of skepticism to help refine the process.”